Giancarlo Benedetti shared with us an idea he uses to help calculate how everyone did.

Freeform Games murder mystery blog

Prizes Galore!

Suggestions for prizes (and prize categories) from our customers.

Alternate Pickpocket rules

One of our customers, Rob from Canada, wrote to tell us about a variant for our pickpocket rules that he used. Watch out - there's a pickpocket about! Here’s the text that he prepared for those with the pickpocket skill: Your character has the Pickpocket ability. Your ability card shows what you can pickpocket and how many attempts you have...

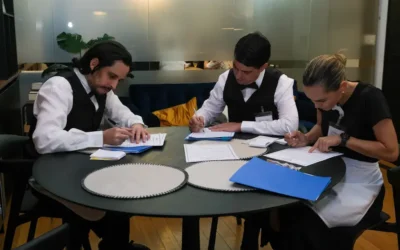

Keeping Score

“Every now and again we are asked if we have a way of assigning points to goals so that our guests can keep score. While we don’t do this normally, this is our suggestion…”

Investigating Pickpocket Crimes

Pickpocketing can be a divisive mechanic amongst experienced freeformers (although I’ve never heard any of our customers complain about it). On one hand it’s a useful mechanic for replicating a real-life skill (one that is thankfully rare); on the other hand it can be particularly demoralising to have spent all game trying to get hold of...

Big Money

I experimented recently with printing our money at approximately life-size, and it looks really good - and feels much more like money. This experiment was inspired by the photograph above from Way out West. Sent to us by Jaqui French, I was intrigued by the dollar bills. Those look like the graphics from our money cards, but printed extra...

Playing two characters

I recently played in UK Freeform’s annual weekend game. Last year it was Cafe Casablanca (Mo played and I helped run it). The year before we both played in The King’s Musketeers. And this year it was Lullaby of Broadway: Into the Woods. As you might guess by the title, Lullaby of Broadway: Into the Woods was based on Broadway musicals - lots of...

Creating a crowd out of unused characters

Note - this is a thought experiment for experienced hosts and players. I've yet to try this out - so I don't know if it works. There’s a style of freeform/larp known as a “horde” game. These normally involve six to eight “core” characters and typically dozens of smaller roles. The players playing the fixed characters stay with those characters...

Real-world alternatives for some of our mechanical ideas

We provide safe, simple rules in our murder mystery games, but sometimes it’s fun to make those rules more closely align to the real world. Here are some examples. These first two are from Denise Knebel in the USA. The secret cupboard One of our games (I’m not going to say which) has a secret cupboard which is normally managed by the host. Here’s...

Rules for Locations

A Heroic Death introduced a new concept for us - locations. And with locations comes rules for using them. We’ve since also use them in Lord and Lady Westing’s Will, and also the 7 expanded characters used for Murder at Sea. While each game will have its own specific location rules to suit that particular game, these are the rules upon which they...